Good Governance Lives at the Heart of Humane Tech

Exploring humane tech metrics and building caring, scalable technology

We gathered on Wednesday evening in San Mateo, ready to explore how technology reflects the choices we make. The evening opened with a simple check-in question:

When did you last feel cared for, connected, present, or fulfilled?

Then we turned our attention to technology. I wanted to ground us in a simple diagram I’ve come back to again and again:

It was a way to see where our choices—how we build, who owns the code, and what we center—land on the spectrum of care and harm. This is why whenever we kick off a humane tech session, we start by connecting with ourselves and each other, sharing what’s truly important to us and really being heard. From there, we had a three-part focus for the evening: getting on the same page about where we are today, not as a talk but as a conversation; sharing more about my own background and why I care about these questions (you can read more about that here); and finally, bringing our skills and awareness to the frameworks and metrics that can help us see the human impact of our tools.

Dignifi: Helping people just released from prison access the resources they need

Danny and John joined us via Zoom to share Dignifi, their AI tool for people returning from prison. Dignifi incorporated in February, and Danny knows the system through personal experience. Their platform guides users through housing options, job leads, and digital literacy. Their goal is to “bring reentrants, service providers, and policymakers into one ecosystem to ensure dignity, accountability and success in reentry.”

As we watched their demo, I asked the group to imagine themselves in the user’s shoes:

Do you feel cared for?

Do you feel connected?

Do you feel present?

Do you feel fulfilled?

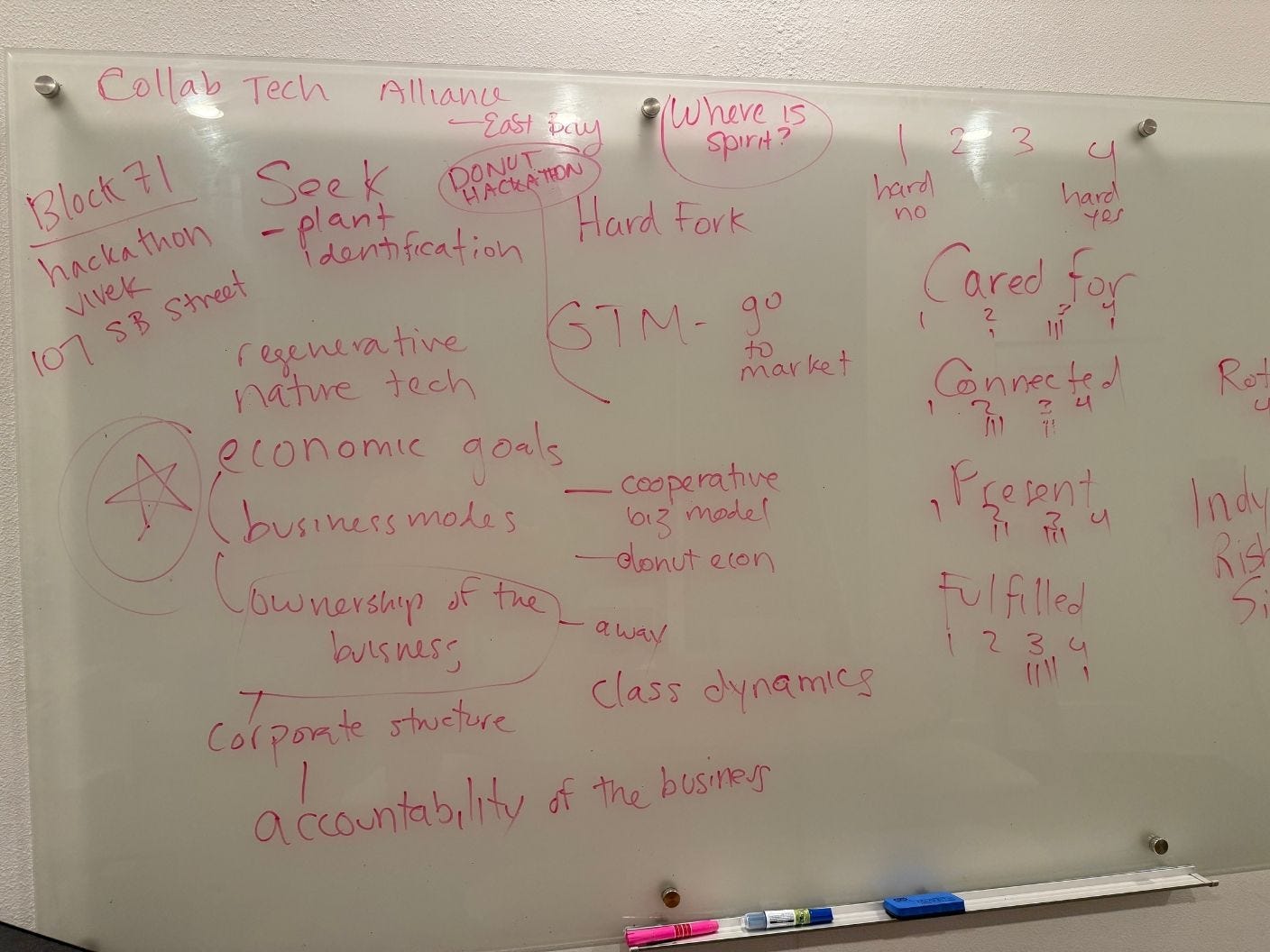

After their demo, we applied the humane tech metrics on the whiteboard:

1 = hell no 2 = soft no 3 = soft yes 4 = hell yes

The four promises of humane tech offered a shared lens for rating a recent digital experience. No comfortable middle ground; each number asked for a clear sense of how a tool met these basic human needs.

A Stanford grad in Human-Computer Interaction said, “I’ve never thought to judge tech with cared for, connected, present, fulfilled. It’s such a sharp heuristic. I’m taking it with me.”

The exercise did what it was meant to do: invite honest, embodied feedback that goes beyond feature checklists.

Cared for - 3

“The tone already feels supportive.”

Connected - 2.4

“The AI experience still feels a bit cold.”

Present - 2.6

“Clear next steps keep attention anchored.”

Fulfilled - 3.2

“Potential is there, but it’s early days.”

Based on the scores, John and Danny committed to refocusing their efforts on care. For instance, one attendee, who works in customer support, shared how she balances empathy with information, and that she’d like to see that in the Dignifi experience.

Can a product stay caring if those who use it don’t have a stake in how it grows?

Beyond the interface: ownership, culture, and my own roots

We turned to the bigger questions: who owns the code, and what does that mean for how humane it can be? Someone shared how cooperative ownership in regenerative farming changed not just what they grew, but how they related to each other and the land. The same applies here: Governance shapes design more than any interface ever will.

We brought in Donella Meadows’ leverage points, focusing on the deepest lever: paradigm. The whiteboard filled up with cooperative models, public-benefit corporations, and community trusts. The absence of cooperative finance in most MBA programs became a quiet signal of what’s valued and what’s not.

Culture came up again and again. It’s not just about what’s on the screen. It’s how we treat each other as we build, and how we decide what matters. It’s nuanced, messy, and essential. For instance, here’s our field guide to how we work together at Storytell.

I was born on an archetypal hippie commune called The Farm. Even though we left when I was young, it held a long shadow and the ways people interacted—humanely and inhumanely—shape how I think about technology and its potential for care or for harm. My family’s approach to technology didn’t start in code, but in how we built physical structures, how we shaped agreements about living and working together. Those early experiences still shape how I think about technology and its potential to care for us or to harm us.

Another builder noted how funding shapes design. Why would a companion bot ever tell you to take a break if the company behind it gets funding based on engagement? Change the funding, and the nudge changes too.

Building the open-source framework

I showed everyone our open-source framework for humane technology: a GitHub repository full of frameworks, my own and others, to gather what’s otherwise scattered across the internet. It’s still in its infancy. You can think of it as an invitation to see what’s already working and to contribute frameworks or thought leaders you don’t see but should be there.

The repo includes a living library of externality frameworks, humane design practices, humane tech metrics and humane linter to run on your codebase that looks for deceptive patterns. Each contribution, whether it’s a pull request or a new question, feels like another step toward weaving together a more accountable, transparent, and human-centered approach to technology.

Give & Get: mapping a supply chain for care

We closed with a quick give & get round. Builders offered user-testing hours and intros to cooperative alliances. In return, folks asked for values-aligned capital and mentors who’ve navigated regenerative revenue models.

As one participant shared, “It’s rare to find people working on the same question from so many angles. Everyone brings a superpower.”

Reflection: the paradigm beneath the code

Each conversation circled back to a single insight: the shape of a company shapes the soul of its product.

Screens can soothe or exploit, but ownership, incentives, and culture steer them long before the first design sprint. Without changing those foundations, “humane tech” risks becoming a brand mask.

Two questions stay close:

What would cooperative or community-owned AI look like at scale?

Could a parole-reentry guide, a plant-ID app, or even a chatbot run on a model where the people it touches also shape its future?

Experiments in democratic ownership, whether unfinished or ongoing, hold part of that answer. Each story shared adds to the slow work of building something different.

Gratitude

Special thanks to UpHonest Capital for supporting this ongoing effort in creating technology that pays attention, as well as Christine Zhang for helping to run the show, and my family for making space in our home.